Being a Therapist On a Psychedelic Clinical Trial: What Is It Like?

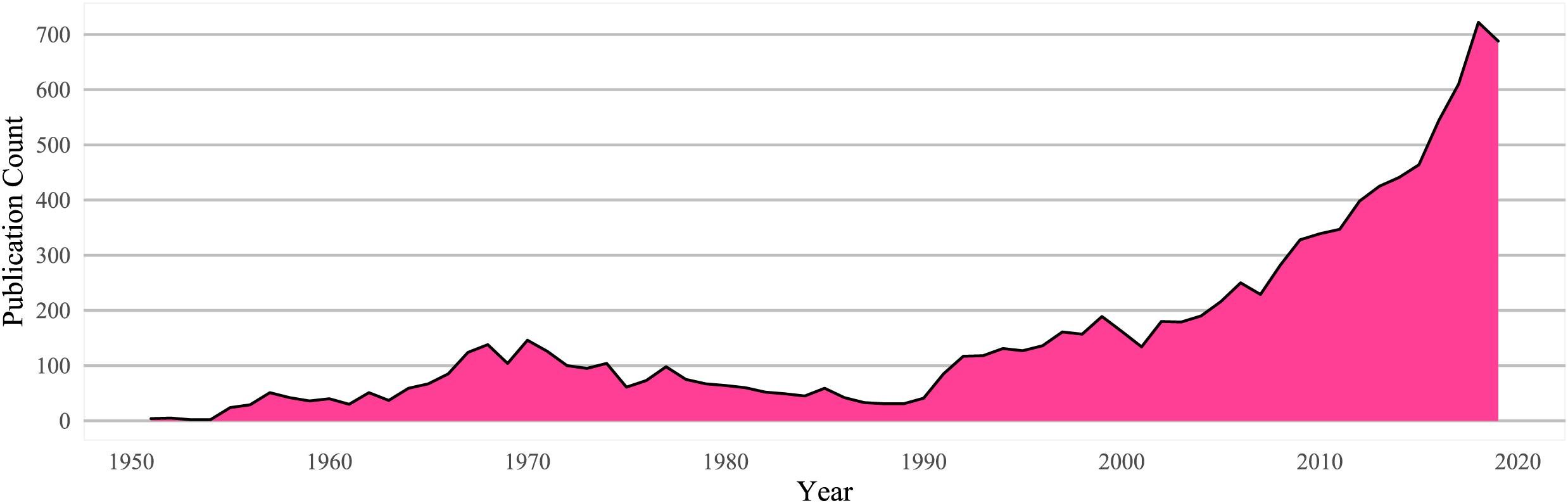

There has been a huge increase in psychedelic trials over the past 15 years. As more trials around the world enrol participants, and more jurisdictions license psychedelic medications and MDMA, there has been a rise in the need for trained therapists to deliver these treatments.

Clerkenwell Health is a global leader in psychedelic clinical trial delivery. We have recruited and trained dozens of therapists to deliver psychedelic-assisted therapy on our trials, and hundreds of practitioners through our Foundations Programme.

We are often asked by therapists what it’s like to deliver psychedelic-assisted therapy in practice. In this interview, I spoke with Clerkenwell Health’s Clinical Director, and Director of their Training Programmes, Dr. Iain Jordan, to get an idea of what it’s like to deliver treatment on these trials.

Zofia Krajewska: How does a therapist end up working on one of our trials?

Dr. Iain Jordan: The most important thing for us is that our patients receive the best possible care. So, there is a comprehensive, multi-stage skills assessment and interview process, where we observe therapy skills in mock scenarios, and then do a more traditional interview.

ZK: Is that process done for each trial that they’re a part of? Or just for their first one with us?

IJ: Once we're satisfied that a person is a highly skilled therapist and that they have the required qualifications, then they can work on any of our studies.

ZK: And how do they get selected to be interviewed?

IJ: We advertise on our website, newsletter, and LinkedIn whenever there’s a new trial. We also have a huge therapist community who we reach out to as well. We now have almost 30 therapists working on contract across our different studies.

Some studies will have particular requirements in terms of training or experience. For instance, we ran a trial on alcohol use disorder and psychedelic-assisted therapy recently, which needed two therapists present with a patient. One needed to have experience in both CBT and the treatment of addiction, and the other preferably had experience with psychedelics.

ZK: And do a lot of trials require previous experience with delivering psychedelic-assisted therapy?

IJ: Not necessarily. Some do. My view is that the quality of the therapist is much more important than their own psychedelic experience. But, of course, if you're a skilled therapist and you have this experience, that may also be beneficial.

ZK: How many therapists work on each trial?

IJ: There are typically somewhere between three and six therapists on each trial. Most of these are therapists on contract, who continue to work in the NHS or in private practice, and we also have two therapists who are permanent members of staff who work across all of our studies.

ZK: What is the time commitment for working on such a trial?

IJ: There's quite a big upfront time commitment where therapists receive study specific training, which can be upwards of 30 hours of training, some of which is online, like watching recorded material, reading written material online, online training sessions, or live training sessions, and some of which is sort of supervision.

ZK: And the time commitment for the actual trial?

IJ: It is really up to the person. Ideally, people would give us at least one dedicated day a week. We need some flexibility from people because it's really complicated to schedule visits in these studies.

ZK: Do therapists also get paid for the time spent doing the training? Or only for time spent with participants?

IJ: Yes, they're paid for the training in all the studies that we've run. And they're also paid for any visit – including dosing, preparation, and integration visits.

ZK: How many participants, on average, does each therapist take on for trial?

IJ: Our lead therapist, who has been with us the longest, has on average at least one dosing session per week and sometimes two or three. Some studies have a single dosing session, which might be half a day or a full day, but they'll have lots of preparation and integration sessions which are 60 to 90 minutes each, before and after. There would typically be three preparation, one dosing and three integration sessions. Some of our studies have much more than that and some have fewer, so, the number of simultaneous patients that a therapist sees is fairly low because they are very intense sessions, especially the full-day ones. So, any more than two of those a week can really take a toll, especially when you add working across multiple trials. Our contracted therapists typically have one participant at a time.

ZK: Does a patient stay with the same therapist for their entire enrolment in a trial?

IJ: That’s always been the case in our studies. However, that’s not always possible, so it’s not completely prohibited by the study protocols, but we would only do that in exceptional circumstances, to maintain continuity of care and develop a therapeutic alliance with therapists, which is an important factor that impacts outcome.

Many trials will have an open label extension part. So, if a participant was in a placebo control group, they will be able to be enrolled in this part of the study. Sometimes, a participant might then elect to have a different therapist in this second part.

ZK: Do the therapists you contract work on multiple trials?

IJ: Most of our therapists also work elsewhere, so they usually don't have time to see multiple participants at the same time. But some people are on more than one study. The training is a really big commitment. If you’re going to have to do 100 hours of training to be across two or three studies, then that's not always possible.

ZK: About the pre-trial training, do you have a limited time to do it? Would it be possible to complete it during the weekends?

IJ: Yes, most of the training can be done in your own time.

ZK: To what extent would it help a therapist to take part in our publicly available training programme, if they want to take part in our trials?

IJ: Our training program will cover some of the same materials as training for a trial, and it can be a valuable signal to employers to show interest in the area. For us, the most important thing is that the therapist is highly skilled and great to work with.

The training programme is relevant in the sense that we cover a lot of important safety and ethical considerations, which are highly relevant for clinical research, and then there are some other components of the training programme that are probably more relevant for people with just a really deep interest in the area, such as proposed mechanisms and results of existing research.

ZK: If someone isn’t selected to work on our trials, would you say there are a lot of opportunities in the UK to work on some other studies or trials?

IJ: Yes, for sure. People should look at the different research sites that deliver psychedelic trials and uh look at the different universities that run psychedelic therapy research or psychedelic system treatments. Clinicaltrials.gov is a good resource as studies will usually list the sites where they are being run. You can also sign up for newsletters of psychedelic research departments at different universities, like Imperial, and that’s a good way of keeping up to date for when they’re recruiting. I know for instance that Imperial will be recruiting for some psychedelic studies of addiction in the coming months, and we often have new studies that we recruit for.

ZK: Great, thanks Iain.

Interested in learning more about psychedelic-assisted therapy?

To contact us with questions or comments, reach out to training@clerkenwellhealth.com.